Neuroscientist by day, David Eagleman’s work of fiction, Sum, was an international bestseller.

Anthony Brandt, Professor of Composition and Theory and Chair of Composition and Theory at the Rice University Shepherd School of Music.

“Runaway Species” by Anthony Brandt and David Eagleman

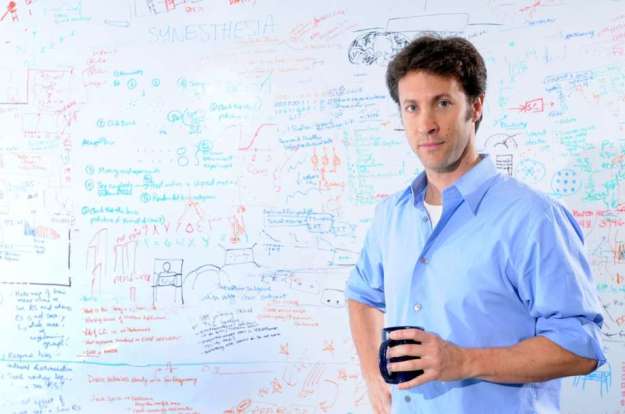

David Eagleman is a neuroscientist and an adjunct professor at Stanford University, best known for his work on brain plasticity, which has led to television appearances and programs, and, of course, best-selling books. He’s also a Rice University alum and former neuroscientist at the Baylor College of Medicine.

Anthony Brandt is a composer and music professor at Rice University, the recipient of a Koussevitzky Commission from the Library of Congress and a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. He’s also the founder of Musiqa, Houston’s contemporary music ensemble.

They combine their interests and talents in the book “The Runaway Species,” a fascinating look at creativity across diverse disciplines. The pair will discuss the book at 7:30 p.m. Thursday in the Christ Church Cathedral, but in advance of that appearance they took some time to talk about how they connected, the future of creativity and a dog that glows red under ultraviolet light.

Q: How did a music professor and neuroscientist come to collaborate?

David Eagleman: Anthony and I have known each other for a while. He’s a music professor, but he’s been interested in how music interacts with the brain, and we met at a conference. We had coffee one day, began discussing creativity, and we decided to write a book on this topic. Three and a half years later, this is the result.

Q: You use a framework for creativity in your book, and you discuss the concepts of “bending,” “breaking” and “blending.” Can you discuss these?

Anthony Brandt: “Bending” is taking a source and messing with it in some way, as when a jazz band plays the same song they played every other night, but they do it in some other way. It’s a variation on a theme. “Breaking” is when you take a whole, break it apart and assemble something new out of the fragments. In the book, we use the example of Picasso’s “Guernica,” in which the artist used bits and pieces of animals, soldiers and civilians to illustrate the brutality of war. And “blending” is any time you are marrying two or more ideas. In the book, we have an example of “Ruppy the Puppy,” the world’s first transgenic dog. He has a gene from a sea anemone, and he turns a fluorescent red under ultraviolet light.

Q: Writing can be hard work, but it seemed as if you had fun researching examples from all disciplines – art, music, science, marketing – to illustrate this three-part framework.

Eagleman: Yes, that was one of the great things about the book. We make the argument that in the arts, there is overt creativity, the bending, breaking and blending is right there for you to see. We think the same cognitive operations occur in science, but it occurs under the hood. When you hold your cellphone, it’s just a rectangle, and there’s no way to see all of the creativity that went into making it. What we do in the book is surf between the sciences and the arts and illustrate how the same processes are at work.

Q: Speaking of cellphones, you point out in the book that it’s a product of “blending” creativity.

Brandt: Phones used to be for making phone calls, but the smartphone now blends many functions. Now you have a device on which you can watch movies, surf the web, use GPS, listen to music and check your emails. All of these functions are married together in one instrument.

Q: The book also describes tension in the human brain between being drawn to the familiar and the lure of exploration. Can you elaborate on that?

Brandt: People aren’t the same in the way they balance novelty and familiarity, but everybody has creative software running in their brain, and they are all capable of aligning themselves on that creative spectrum and being participants in it. But the diversity in this tension, between exploration and familiarity, is healthy. We want a range of people, some of whom are pushing the envelopes, others who are holding back. We don’t want to rush headlong into every wild idea, but we also don’t want to stay rooted in one spot, never improving our lot.

Q: One animal highlighted in the book is the seasquirt, which embodies both of those tendencies over the course of its lifetime. Early in its life, it commits to exploration, but later in life, it adopts familiarity.

Eagleman: (laughs) The seasquirt, early on, uses its brain to explore and to find a suitable habitat. But when it finds that habitat, it eats its own brain for nutritional value.

Q: That’s an extreme case.

Eagleman: Yes. The lesson is not to eat your own brain. It doesn’t promote creativity.

Brandt: But it’s also a good distinction between lower-order animals and humans. Humans have a special neural architecture, one that seeks exploration, and creativity is a way to make that manifest – to take what’s going on in our minds and bring it out to the world. Creativity is the exploration of unknown territory. And whether it’s creating a recipe, a musical rift or a patent, humans are exploring all the time.

Q: This tension is also captured by a “skeuomorph,” which you discuss in the book.

Eagleman: It’s a graphical object that represents a real-world object. They keep a hand on the past, while introducing something new. One of the examples we use in the book is that computers still use an icon of a floppy disk to save documents, even though floppy disks haven’t been used for 20 years. The skeuomorph illustrates this tension between the novel and the familiar. We want to see something familiar, but we also want computers to lead us into the next century.

Q: Can we create computers that are creative?

Eagleman: I think it will be possible. The human brain is a machine, it’s a vast and complex machine, so there’s no reason, in theory, why we couldn’t make creative computers. What humans do is to try to surprise and impress others. If you want to build good artificial intelligence, build a society of AI agents that are all trying to surprise and impress one another.

Q: Will we become redundant?

Brandt: I think the good news on that front is that most of the AI right now is gobbling up repetitive tasks. The things that computers love to do are things where the same input leads to the same output. The jobs that are most at risk right now, are the jobs that involve repetitive tasks. Creativity is a social enterprise, and humans are social, and it is this quality that has fueled our creativity over the ages. It will be interesting to see what happens when you bring a machine into that social sphere and whether we even accept the computers’ incursion in that way. It’s an open question.

By Mike Yawn

Source: houstonchronicle

Visit us at First Edition Design Publishing