How do you become truly great at something, one of the best in the world? Or at least better than you are?

Many people believe that greatness comes from talent and natural inclination. They believe that great athletes and artists are born, not made, and so what’s the point in trying if you’re not naturally talented?

I used to believe that, too, but everything changed for me when I discovered practice, the idea that not only can you become great through your own efforts, but that all of the best writers, musicians, painters, and athletes in the world have done the same.

In this guide, we’re going to be exploring how you can become a better writer by following the principles of deliberate practice (this is The Write Practice, after all), but generally, how you can improve your skill level in any field.

We’ll look at the four components of deliberate practice that will make your practice time actually work. Finally, we’ll get a chance to start actually practicing our writing through a creative writing exercise.

Ready to accomplish your writing goals? Let’s get started!

Are Great Writers Born or Made? (In Other Words, Does Practice Really Matter?)

Like many people, as a young, aspiring writer, I believed that great writers were talented, that they had an innate ability for writing that all but predisposed them for success.

There was a problem with this mindset, though, because every time I received negative feedback on my writing, it made me question whether I had enough natural ability. Could I succeed at a professional level when people were criticizing my best work?

Sometimes I would get so discouraged I would think I should just quit. But then, just in time, someone would praise my writing and I would go back to believing I was a genius destined for greatness.

And this is the problem with having a fixed mindset in which you are born with a certain amount of natural ability that predetermines your performance. Instead of being able to use feedback to improve your skill level, you become very vulnerable to it.

When I instead adopted a growth mindset, believing that the most important criterion for my success was the amount of effort I put into practice, it changed everything for me.

This mindset helped me to focus on what I could control—my focus, persistence, and the coaches and mentors I surrounded myself with—rather than what was outside of my control, namely whatever innate talent I did or did not have.

It transformed my life so much that I started a whole community around it, The Write Practice, to help others accomplish their writing goals through deliberate practice.

But there is good practice, practice that will help you actually succeed in your writing life, and there is bad practice that will just lead to a lot of hours wasted. What are the components of deliberate practice, and can you make sure you’re practicing effectively?

If you want to become a great writer, you need to develop a deliberate practice. This article shares four components you should add to your writing practice.

Tweet

What is Deliberate Practice? Definition of Deliberate Practice

>Deliberate practice is the effortful, structured, repetition of tasks for the purpose of improvements of performance beyond a current skill level.

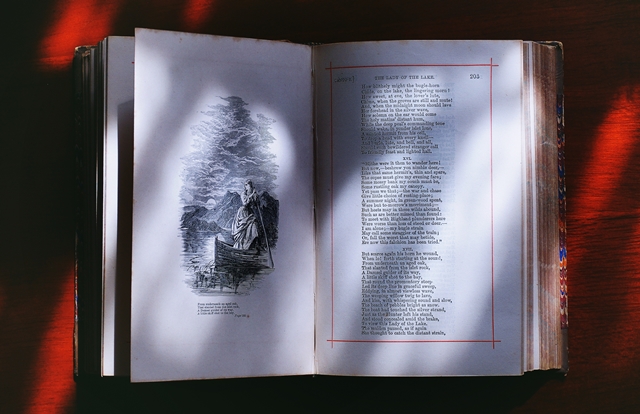

The term deliberate practice was first coined by psychologist K. Anders Ericsson and a team of researchers to describe why some classical musicians achieve elite performance and others don’t. In their study, K. A. Ericsson et al stated that those with expert-level performance in music had at least 10,000 hours of practice over the course of their lifetimes.

Malcolm Gladwell then popularized this into the “10,000 hour rule,” or about ten years, in his book Outliers.

As Ericsson says, “This is based on findings from a wide range of domains where research has suggested that a minimum of 10 years of goal-directed, hard work is required for an individual to reach a level of expert proficiency.”

The 4 Components of Deliberate Practice

There are four deliberate practice principles that you must follow if you want to reach expert-level performance. Namely, deliberate practice is structured, effortful, and requires feedback and repetition.

Here are the four things you need to develop an effective writing practice:

1. Deliberate Practice Is Structured

Deliberate practice is a structured activity with the explicit goal to improve current level of performance. For example, if you have the goal of becoming a better basketball player, simply playing a lot of basketball may lead to improvements in performance. However, incorporating drills, exercises, and other structure methods to develop certain aspects of your game will lead to much faster improvements in actual performance.

The same is true for writers. Spending a lot of time writing will certainly help you become a better writer, but having a specific focus when you write will help you improve faster. For example, you could focus on show don’t tell one writing session, or when you’re editing, you could focus on crafting more realistic dialogue.

Purposeful practice focuses on one aspect, one specific skill, not the entire craft at once.

Also, the exercises must also be tailored to your current level of skill. That means that having a coach or teacher who can direct you to the right focuses for your skill level is helpful.

As Daniel Coyle says in The Little Book of Talent, “There is a place, right on the edge of your ability, where you learn best and fastest.”

How to Apply It To Your Writing:

- Use short, structured writing exercises (like the ones we have daily on The Write Practice) to practice specific writing skills.

- Write several short stories. Short stories have traditionally been the training ground for writers.

- Whatever you do, finish your writing pieces (e.g. novels, essays, nonfiction books, short stories, articles). If you don’t finish, you fail to through each phase of the writing process and miss many practicing opportunities.

2. Deliberate Practice Is Effortful

When you hear that you need 10,000 hours to become a top-level performer in a field, whether it’s writing, music, athletics, or accounting, you might think that all you have to do is put in the hours and you’ll reach all of your goals.

However, Ericsson calls the type of practice that is just about putting in the hours “naive practice” as opposed to deliberate, focused practice. Naive practice, he finds, doesn’t lead to superior performance. Instead, it ends with relative mediocrity.

In other words, you can’t journal your way to becoming a great writer.

You can’t journal your way to become a great writer. Great writing comes through deliberate, effortful practice.

Tweet

How to Apply It To Your Writing:

- Write a piece you can publish. Journaling in private is cathartic, but extended writing for public consumption forces you to put in the effort required to get better.

- Again, finish your writing pieces. Writing until “The End” takes effort, but it’s what’s required to get better.

- Join a writing contest like this one.

3. Deliberate Practice Requires Feedback

Without expert feedback, without someone looking over your shoulder to see what’s working in your practice and what’s not, you simply won’t improve.

You can practice for 100,000 hours, but without constant feedback, your skill level will plateau.

This was the biggest game changer for me in my writing. As I mentioned, I used to view negative feedback as a threat to my talent.

Once I adopted a practicing mindset, though, feedback became my greatest resource.

How do you get feedback? In the writing field feedback comes from three places: expert feedback from editors and other professionals, peer feedback from other writers, and audience feedback from readers. All are incredibly helpful and can lead to lasting change, but expert and peer level feedback should be prioritized.

Most of all, take all feedback graciously, accepting what you can learn and letting go of what isn’t helpful for you in that moment. Remember that consistently negative feedback doesn’t mean you’re a bad writer or, even more, that you never will be a great writer. It just means that you need more practice!

How to Apply It To Your Writing:

- Share your practice and your finished writing pieces with other writers, for example, in the Write Practice workshopping community.

- Hire a developmental editor to give you feedback on your first book.

- Get beta readers to receive audience feedback.

- After you write something, don’t hide it in a drawer. Publish it! What can you learn from the feedback you receive?

4. Deliberate Practice Requires Repetition

Wash. Rinse. Repeat.

We get better through consistent practice, by repeating the above steps hundreds, even thousands of times.

Stephen King famously wrote hundreds of short stories that were rejected by editors before his first one was published. He would put a nail through rejection letters until he had a stack of them almost as long as the nail. Then he would start the next story.

In the same way, to develop your creative skill, you need regular practice. Writing one story, one book, one blog post, one essay isn’t enough. Instead, once you’re finished with one book, start the next one.

There is something freeing about this. So many people treat their writing as this thing that must be perfect, and it freezes them up, causing writer’s block and a host of other problems.

What if your writing doesn’t have to be perfect? What if it could just be practice? How could that change your mindset, helping you to write more and become a better writer faster?

How to Apply It To Your Writing:

- Practice consistently! That’s why we post one new writing exercise every day, to give you the chance to practice. Subscribe here.

- Join the 100 Day Book program and finish a book through a proven process. Then, when you’re finished, write another book using the same process!

Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Motivation

This is also where intrinsic motivation comes in. If you are running off only extrinsic motivation, external rewards, you will quit. You won’t have enough driving you to keep showing up when the work gets hard.

No, the people who succeed are intrinsically motivated. They have the grit and persistence to keep going because they are driven by the work itself.

I love this quote from Robert Green, which I think speaks to this level of commitment. He says,

“Engaged in the creative process we feel more alive than ever, because we are making something and not merely consuming, masters of the small reality we create. In doing this work, we are in fact creating ourselves.”

Do you have this level of motivation for your practice? Could you develop it?

How The Write Practice Can Help You Become a Better Writer

How do you practice writing?

At The Write Practice, we truly believe that everyone can become a great writer through deliberate practice.

Over the last ten years, we’ve published thousands of lessons, created hundreds of hours of videos and trainings, and led dozens of writing courses.

In that time, we’ve helped millions of people learn new writing techniques, write books, get published, and accomplish their writing goals.

We’d love to help you too.

Every day, we post a new writing lesson and exercise, giving you the chance to learn something new and put it to practice immediately.

If you’d like to practice with us, sign up for our writing community or consider starting your first practice exercise below.

Happy practicing!

So how about you? Are you willing to put in your 10,000 hours? Are you willing to practice writing deliberately? If you are, then you’ve come to the write place . . . oops, sorry, bad habit!

By Joe Bunting

Source: thewritepractice.com

Follow us on Facebook and Twitter

Visit us at First Edition Design Publishing