Every time we sit down to write, our mood and state of mind affect our words. We infuse, to some extent, everything we write with our unique “voice.” Our emotions come through on the page.

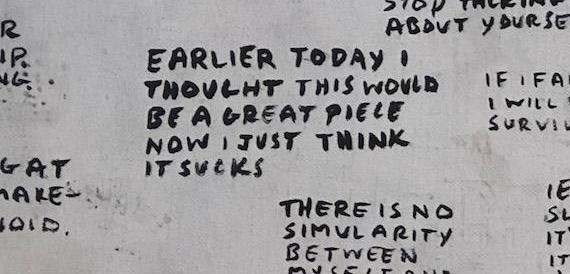

When we’re struggling to eke out even a few words and make sense of our writing, it shows in our work. Our characters are flat. Our scenes are dull and passive. Our plot is thin and weak. Nothing we try fixes the problems. Or, maybe words don’t come at all.

We may declare that we have a case of writer’s block, particularly if we’ve wrestled with the vexation for weeks or months. But, there may be a stronger and more insidious obstacle: shame.

What Is Shame?

The kind of shame that can affect your writing is invasive, corrosive, powerful, and debilitating.

Shame is beyond embarrassment and sadness, although both may be present. It’s beyond writer’s doubt. It tells us we are defective and unworthy of joy, happiness, and reaching our goals. It’s the gnawing feeling in our solar plexus that we’re not okay, and anything we do is not okay. We feel as though we are a mistake rather than acknowledging that we made a mistake.

Shame can exacerbate or bring on depression and anxiety. I have lived with depression and anxiety my whole adult life, and I realize they can render me emotionally raw or destitute. These conditions magnify and intensify when I’m wrestling with my imagination. Combined, they mix a recipe that can shut me down for days.

Writers and Shame

When we feel helpless and vulnerable, our writing can take on a tentative and cautious tone. We may be afraid to write with honesty, thinking we’re too exposed or that our writing could harm others. That struggle to write can feel like writer’s block.

We don’t lack imagination. Rather, we lack self-compassion that allows our imagination to shine through.

Having self-empathy helps us see ourselves as we truly are and acknowledge that everyone is imperfect and makes mistakes.

Conversely, we may say on the page what we can’t openly verbalize. Creative writing, whether fiction or nonfiction, can provide an outlet for pent-up emotions. Passion-charged words act as release valves for the writer and have a ring of authenticity and strength.

But, we must take care not to get stuck in an emotion which then drives all our writing.

Perhaps every scene is punctuated with anger, frustration, sadness, or desperation. Even tender, nurturing, quiet scenes somehow sound angry. Or, maybe, every scene sounds flat and emotionless because we’re avoiding confrontation with strong emotions within us.

It may be time to check our emotional state. This goes deeper than simple writer’s block. We can’t manage what we don’t know exists.

What Can We Do About Shame?

There are four powerful strategies for addressing shame.

1. Take steps to recognize shame

We first must acknowledge that the presence of shame is a possibility. We recognize the shame by looking at painful experiences in our lives, how we’ve coped with them, and the ways they continue to affect us.

Shame can show up in our lives as overeating, sleeplessness, outbursts, smoking, drinking too much, or using illicit drugs.

It may shut us down, or we may become super busy as we attempt to mask painful feelings.

It may wreak havoc on our relationships.

By bringing shame to the forefront, we can begin to deal with it.

2. Realize you are okay

Second, accept that there’s nothing wrong with you.

If you experienced an act perpetrated against you, know that you’re not at fault. You are dealing with the aftermath of emotional devastation.

Most of our life experiences are beyond our control.

Distraction activities may make us feel worse than before we engaged in them.

If you acted in a way that harmed someone else, know that you did the best you could at the time and try to find a way onto the path of self-forgiveness. Beating ourselves up compounds the pain. You may have to contend with the consequences of your actions, but you now can view the episode from the vantage point of humility.

It’s crucial that you know, really accept, that you are a precious, worthy human being.

3. Talk about it

Third, enlist the intervention of a professional or a trusted, supportive, nurturing person — psychologist, counselor, mental health therapist, minister, rabbi, priest, spiritual director, or trusted friend or relative. We must confront the shame in a process that works for us, but we don’t have to do it alone. Check resources in your community for the type of counseling you need.

I regularly meet with a psychologist to sort through the pain of trauma and the resultant emotions. I have, in the past, consulted with a spiritual director as well. They help me gain clarity and a sense of empowerment. They act as mirrors for me and see what I can’t — I’m too close to my own stuff.

4. Write about it

Fourth, writing about the experience helps get it out of our head and in front of us where we can examine it without judgment.

You already have a set of tools and techniques in your writing arsenal. These strategies come in handy for journaling.

Ask questions to get started. What am I feeling right now? What do I want to do about it? If I choose to act now, what are the possible outcomes? How can I work through this? These questions will generate others.

Our journal can be as simple or as elaborate as we like. I have a favorite brand of leather-bound, lined journal that has 384 cream-colored pages, each graced with a fleur-de-lis at the bottom. I journal daily and have hand written over 7200 pages since September 8, 2002. I note the date and time of each entry. I use different colors of ink to enliven my writing and add an extra dimension of focus.

You can also journal in a word processing document on your computer or use one of several online journaling programs and apps.

Journaling helps me name the problem, identify the components and my emotions, and release strong feelings. It helps ground and center me, and is an excellent complement to my therapy sessions. I often discuss a journal entry in therapy, and I just as often journal what we discussed in a session.

Consider your threshold for safety when journaling. Protect it and keep it as private as you need to. Show or discuss it with other people according to your comfort level.

Freedom Beyond Shame

Working through the layers of shame can be rewarding and powerful, though neither simple nor easy. The time spent can open avenues and vistas beyond imagination.

Approaching shame with an attitude of healing, rather than trying to fix what happened, will support you and help sustain your efforts. As you overcome shame, you’ll overcome the associated writer’s block, too. Your stories — and your life — will be all the richer for it.

All the best to you as you explore the shame in your life. You and your writing are worth it.

What are some techniques you have for working through strong emotions that act like writer’s block and threaten your writing? Let us know in the comments.

Source: thewritepractice.com

Visit us at First Edition Design Publishing