Last week, I was able to escape the bomb cyclone and travel to Miami. Before you get too jealous, Florida was also experiencing an unusually cold week, and any time spent on the beach involved a sweatshirt and a blanket!

Lucky for me, Miami has much more than its famously beautiful beaches. Its city energy is on par with New York and people travel from all over the world to eat authentic Latin food and experience the art scene. There were tons of museums and exhibitions I could visit (and take shelter from the cold!).

3 Artistic Truths Writers Can Find in The Everywhere Studio

One of the (free) exhibitions I visited in Miami was called “The Everywhere Studio,” which is on display at the brand new Institute of Contemporary Art. During my visit, I couldn’t help but be reminded of my own writer’s journey, The Write Practice, and all of you. Here’s why.

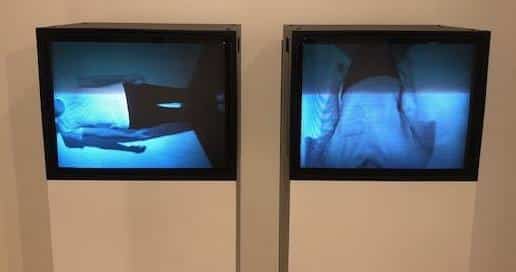

1. The Everywhere Studio recognized that art can be work

One of my favorite pieces of The Everywhere Studio was a video of a man bouncing in a corner like a bowling pin glued to the ground. It was redundant. It was banal. It was, according to its description, a “performance of endurance [that] invokes the idea of art as a form of labor, and not merely creative expression.”

Many times writing is a blast, but other times, we’re literally just trying to meet a deadline or reach our daily word minimum and it’s just work. Or worse, it’s actively boring.

But at The Write Practice we embrace this part of writing as practice because it’s how beginners become good writers, and how good writers become great writers. We know that those moments are an inevitable stop on the road to greatness (or at least completion).

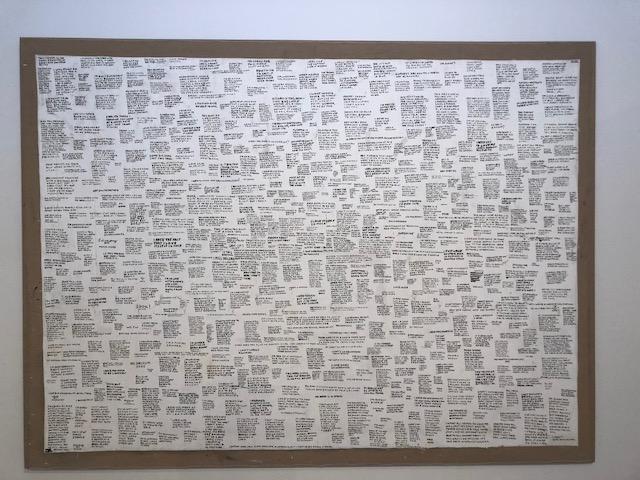

2. The Everywhere Studio had a wall of journal entries

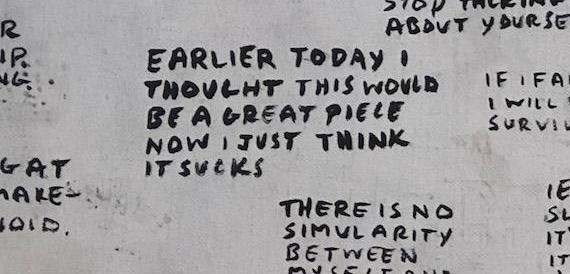

I think most writers would have gravitated toward a grand display of one artist’s thoughts and ideas and doubts and mantras.

Is the journal not the quintessential writer’s studio?

The intro to the The Everywhere Studio noted that the term “studio” has evolved such that many artists can’t point to a physical location where all the art happens. We’re increasingly mobile. And rent is expensive! To me, the journal is a great interpretation of the writer’s “studio.” It’s personal, it’s a mess, it’s incomplete.

Also, I think we all can relate to this gem (a close up of the above piece):

3. The Everywhere Studio created a sense of community

For many artists, especially writers, the process of creating can be a solitary one because often you’re literally alone.

But there are actually a lot of people out there who can identify with the ups and downs of the creative process, which I remembered while visiting The Everywhere Studio. Strolling through the museum, I found myself able to relate to many of the artists’ studio interpretations, which was comforting.

Writers conferences and writing groups are great for finding this sense of community. So is The Write Practice. 🙂

The Art of Museums

Visiting The Everywhere Studio was a fun opportunity to look at my art and my writing in a different way. If you haven’t recently, I’d encourage you to visit a museum or exhibition near you. Don’t limit yourself to learning about just other writers: challenge yourself to find connections between writing and all the other kinds of art and creation you see.

Who knows what new inspiration you’ll discover?

Photos of The Everywhere Studio at ICA Miami are courtesy of Monica Clark.

What museums have inspired you? Or, what’s your writer’s studio? Let us know in the comments.

All the images are taken from https://thewritepractice.com/writers-studio/?hvid=1XdbkC

By

Source: thewritepractice.com

Visit us at First Edition Design Publishing